By Jock Finlayson, ICBA Chief Economist

When future historians assess the economic and fiscal record of the Justin Trudeau government, they are likely to emphasize a few key themes. The first is Canada’s economic stagnation since 2015. Gross domestic product per person, adjusted for inflation, has basically flatlined over the last eight years, with more of the same in store for 2024. That has never happened in Canada since the Depression of the 1930s. To be fair, feeble gains on this core indicator of economic prosperity partly reflect Canada’s robust, immigration-fueled population growth since 2020. Because most newcomers have below average earnings in the first few years after landing, this tends to weigh on average per capita income and GDP. It’s possible we’ll see a rise in per capita GDP as recent immigrant cohorts get settled into their new home and their incomes begin to climb:

A second theme is the weakness of private sector investment. The OECD notes that Canada ranks near the bottom among the 47 countries it tracks in the growth of business investment since the mid-2010s. Canadian companies, collectively, invest less than 60% as much as American businesses, on a per employee basis. Subdued business investment, in turn, is a major contributor to Canada’s notably lacklustre productivity growth. In the mid-1980s, Canada’s GDP per hour – labour productivity – stood at 88% of the U.S. level; today, it’s only 70% of the U.S. level. The relentless drop in Canada’s standing in the global productivity league tables has alarming implications for real wages and household incomes in the future.

Tackling the related problems of sluggish business investment and non-existent productivity growth should have been job one for Budget 2024. Instead, the government chose to boost spending across a wide range of program areas and announced a significant increase in capital gains taxes on affluent individuals as well as corporations and trusts (to the tune of $20 billion over the next five years). Whatever the merits of this proposal, it won’t do much to bolster lagging investment or help Canadian companies raise capital in the domestic market.

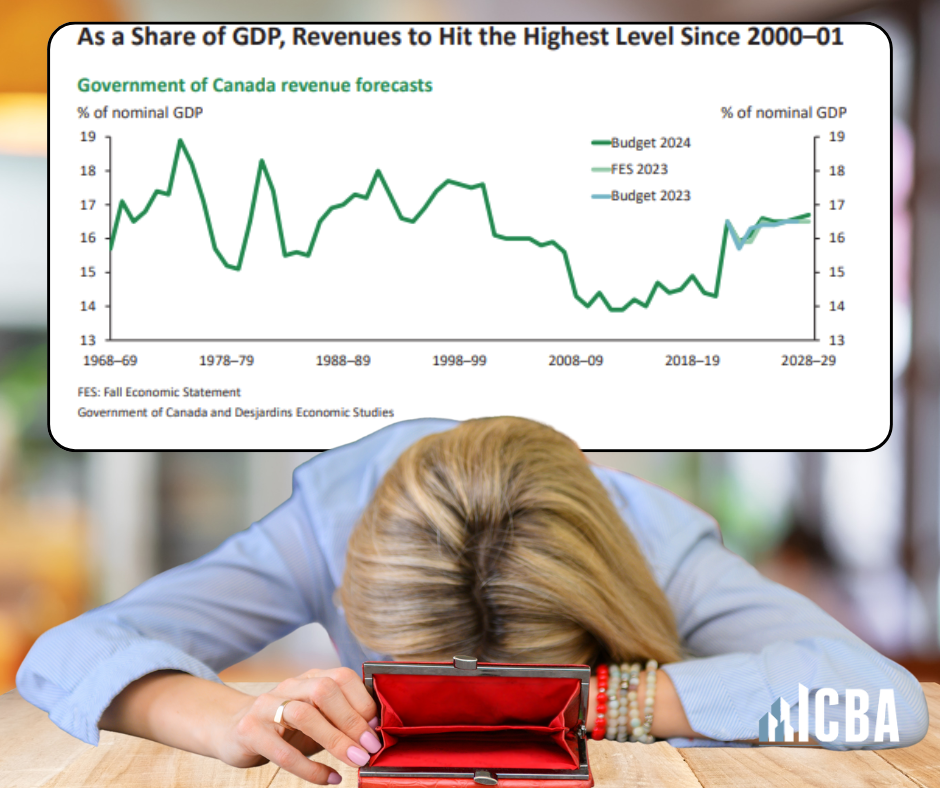

A third theme that characterizes the Trudeau era is fiscal profligacy — big jumps in government spending, chronic deficits, and a soaring debt. Government has expanded its economic footprint, whether measured by spending, regulation, or revenues:

Few governments in modern Canadian history have exhibited a less disciplined approach to managing day-to-day expenditures. The pattern has been particularly stark since the pandemic. To cite one example, Budget 2024 projects that total federal spending in the next four years will be $77 billion more than Finance Minister Freeland was predicting in Budget 2023 – barely one year ago. This year (2024-25), spending will be $16 billion higher than the Minister was planning in Budget 2023. The Liberal government has abandoned any plan to bring Ottawa’s finances into balance, ever. Meanwhile, debt-servicing costs march higher, driven by serial operating deficits and the higher interest rate environment now facing all borrowers.

Budget 2024 confirms that the Trudeau government remains true to form, committed to prodigious spending (notably in areas of provincial jurisdiction) and unwilling to decisively shift its priorities toward improving the business environment or tackling our productivity woes. While it contains a few positive measures, Budget 2024 leaves Canada floundering, lacking a credible “fiscal anchor” and without a convincing strategy to address the country’s increasingly serious structural economic challenges.