By Jock Finlayson, ICBA Chief Economist

The Carney government has pledged to double Canada’s exports to markets other than the United States over the coming decade. That’s a tall order – especially in a world of rising protectionism and mounting geopolitical tension. For Canada, success will require significant changes in several key areas of public policy that influence business investment and location decisions, company growth plans, the productivity of the business sector, and the development and maintenance of infrastructure that supports and enables trade and commerce with external markets as well as within Canada.

The main countries Canada will target in its quest for trade diversification are in Europe and the Asia-Pacific. The latter region is particularly important given that Asia is home to three-fifths of the global population and many of the world’s fastest growing economies.

The efficiency, reliability and overall performance of major ports is a significant factor affecting the global competitiveness of most trading nations. Well-functioning ports enhance the cost competitiveness of the host country’s merchandise exports in international markets. They also reduce the cost of imported goods for domestic consumers and businesses. It follows that Canadian policymakers need a solid understanding of the strengths, weaknesses and global reputation of Canada’s ports if they are serious about pursuing new trade relationships and boosting exports beyond North America.

Unfortunately, as confirmed in the World Bank’s latest ranking of container port performance, Canada is a global laggard in this domain. The World Bank’s report uses an index to assess ports’ performance based in large part on “vessel time in port,” which captures both time at berth and time spent waiting at anchor prior to loading/unloading. The report uses data for 405 global ports which collectively accounted for 175,000 vessel calls in 2024.

North American ports generally put up poor scores, with just one (Philadelphia) making it into the top 30. Within North America, west coast ports rank near the bottom, with Vancouver faring especially badly (ranking 389th globally). Seattle is ranked 271st, Long Beach 318th, and Los Angeles 359th. Canada’s other west coast container-handling port, Prince Rupert, comes in at 362nd, although its standing has improved materially since 2023. Canada’s principal east coast maritime gateway, Halifax, scores much better (55th) than other Canadian ports. See Figure 1 for Canadian port rankings.

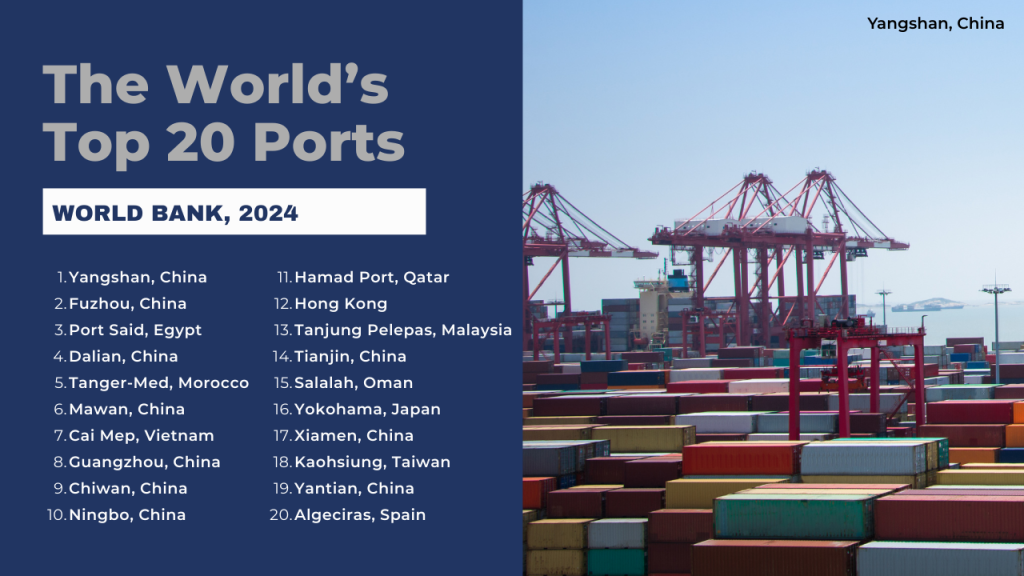

In 2024, 16 of the 20 best-performing world container ports were in Asia (the remaining four are in Spain, Oman, Morocco, and Egypt), with China, Taiwan and Hong Kong dominating the top 20 list. (See Figure 2 for details.) According to the World Bank, “a high ranking reflects above-average fast turnaround times for all vessel and port call categories.” Most of the top performers “are leading export and transshipment hubs.”

The Carney government has identified infrastructure projects as likely candidates for regulatory fast-tracking as part of the Prime Minister’s “build-build-build” agenda to kick start our largely stagnant economy and diversify trade. Expanding capacity and bolstering the competitive performance of Canada’s ports must be a priority for policymakers.

Canada’s west coast ports should be at the head of the list for new investment, technology upgrades, and a commitment to deliver stable and productive labour relations in the maritime transportation sector. As noted by transportation and trade analyst Tim Renshaw, Canada’s transportation system and our “vital Asia-Pacific Gateway need all of the infrastructure and technology improvement they can get.” Ottawa also needs to take action on the labour relations front to improve the actual and perceived reliability of our major trade gateways, notably on Canada’s west coast, where a pattern of strikes and other labour disruptions has imposed significant costs on the country’s economy and undercut efforts to attract more business from shippers.