By Jock Finlayson, ICBA Chief Economist

Canada’s economic prosperity is stagnating, at best. Many readers may feel this, based on their own experiences trying to earn a living or keeping their enterprises afloat. Others may sense it from observing the struggles of their children or neighbours or the health of local small businesses.

This isn’t simply a story about rising inflation and higher borrowing costs since the nadir of the COVID pandemic in 2020-21. It also speaks to deeper problems with Canada’s economy – problems that continue to impede business investment and productivity, and that are now weighing on the growth of real incomes for many households and individuals.

When Justin Trudeau led his Liberal Party to a majority government in 2015, he pledged to support “the middle class and those seeking to join it.” However, judging by the trajectory of inflation-adjusted incomes, his government has done little to bolster the fortunes of the (never-defined) “middle class.”

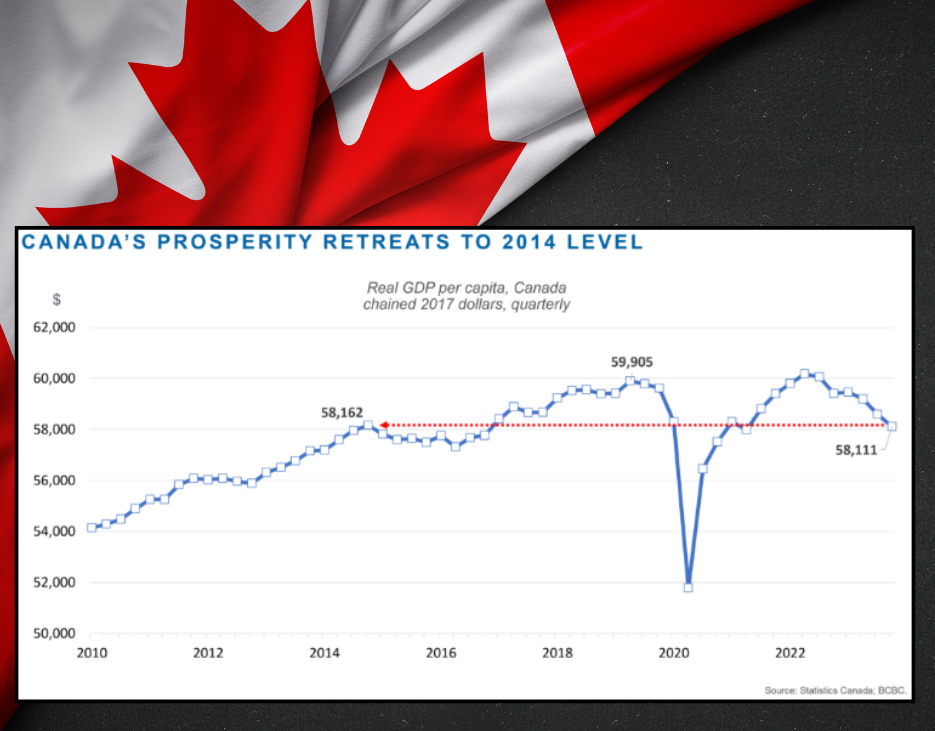

Consider what’s happened to the total output of our economy—gross domestic product (GDP)—measured on a per-person basis. Because Canada has a rapidly growing population, it’s important to factor in demographic change when looking at how much output the economy produces in any given year. All things equal, an expanding population leads to more production and a higher level of overall GDP because the workforce is larger and adding more people automatically boosts the demand for goods, services, and housing.

But the sad truth is that Canada has been lagging behind many of our peers (including the United States, Germany, Australia and the Scandinavian countries) in increasing GDP per person, which is the most widely used measure of prosperity. Before Mr. Trudeau took office, Canada’s GDP per person roughly matched the average for the developed economies as a group. Since then, a widening gap has opened up with other advanced economies, as noted in a recent article by David Williams of the Business Council of B.C.

After stripping out inflation, GDP per person in Canada has been essentially flat since 2014, as shown in the accompanying chart. Indeed, Canada ranks near the bottom among all developed economies in improving this key indicator of economic wellbeing. Yes, the Canadian economy has been growing over most of the past 7-8 years, but this mainly reflects a larger population and workforce coupled with the impact of inflation. When the GDP figures are adjusted to account for population growth and inflation, Canada is losing ground.

And, unfortunately, there is little prospect of a near-term turnaround. Statistics Canada reports that real GDP per person stood at $56,206 in 2019, before the onset of COVID-19. It dropped sharply to $52,741 in 2020, before rebounding over the course of 2021-22 as the economy reopened. But in 2022, real GDP per person remained below the 2019 figure and was scarcely higher than five years earlier. Last year it fell again, amid faltering economic growth and a rapidly increasing population. And 2024 will see a repeat of 2023’s dismal performance:

How will things evolve in the next several years? Using economic growth forecasts embodied in the federal government’s fall 2023 economic statement, and assuming annual population growth of around 2% for the next half-decade (compared to over 3% in 2023), even by 2027 Canadian real GDP per person—again, the fundamental indicator of how Canadians are faring in economic terms—will remain below its pre-pandemic level and at best be only a smidgeon higher than in 2014.

Most Canadian policymakers—including Prime Minister Trudeau and his cabinet—prefer to ignore the reality of an essentially dead-in-the-water economy that’s no longer generating gains in real incomes and living standards for most of the population. That’s not good enough. Canada has the assets, the people, and the natural resources to do better. While the country has been struggling with low levels of business investment for the past 8-10 years, which helps to explain our very meagre productivity growth, that is a problem that can be fixed with smarter public policy. Canadians should insist that our governments devise and implement sensible pro-growth policies that will drive private sector investment, spur productivity, and thereby help to lift the incomes of families and workers in the coming years.